Or: Australia Australia Australia!

From Daily Jocks on the 25th, this example of their own AUS line (with my caption appended):

![]() (#1)

(#1)

A triple threat: proudly

Australian, proudly

Working class, proudly

Queer – “I like to get

Down under with

Me mates”

The company’s ad copy:

Say G’day to our newest underwear collection, designed downunder (for your downunder). Featuring a soft waistband with bold AUS logo and printed Australian flag, the cotton/spandex blend will keep you feeling comfortable.

To come: more on the underwear and the body of the model in #1. Then to Monty Python’s “Bruces” sketch, notes on Bruce as a particularly Australian name (and, in the U.S., as a particularly gay name), with a digression on the wattle, and then to Australian comedian and actor Barry Humphries, Dame Edna Everage, and Aussie bloke Barry McKenzie.

The underwear. #1 has DJ’s AUS underwear in a trunk (with fly). It also comes as a low-rise brief (flyless, more serious pouch):

![]() (#2)

(#2)

The AUSwear is in the blue and white of the Australian flag, but without the Union Jack or the representaion of the Southern Cross constellation:

![]() (#3)

(#3)

The model. The model in #1 has a really fine model’s body: swimmer-type build, really fit, but not ostentatiously developed. Lightly furred, neither notably hairy nor notably smooth. A very good-looking body, also “natural” — a body men can admire and identify with, or (if that’s what works for you) desire. No doubt he’s good for business.

As for the actual man, I doubt that his name is Bruce, and I have no idea whether he is Australian, working class, or queer.

Bruces. From Wikipedia:

The Bruces sketch is a sketch from the television show Monty Python’s Flying Circus, and appears in episode 22, “How to Recognise Different Parts of the Body” [aired 11/24/70]. It involves a group of stereotypical lounging Australians who are revealed to be the Philosophy Department at the fictitious University of Woolamaloo (a misspelling of the Sydney suburb of Woolloomooloo; this is how the suburb is actually pronounced with an Australian accent), and all named Bruce, with a common fondness for beer and a hatred of “poofters” (a derogatory Australian slang word for a homosexual). Terry Jones plays a “pommie” [British] professor, Michael Baldwin, joining the department and meeting his colleagues for the first time.

… Eric Idle co-wrote the sketch with Cleese and said he based it on his Australian friends from the 1960s “who always seemed to be called Bruce”.

You can watch the whole sketch here. It’s laced with stereotypical Aussie slang and stereotypical Aussie admiration for working-class values and behavior (and disdain for their stereotypical British counterparts). The full transcript, so you can appreciate the details:

Voice Over: Number eight. The kneecap

Pull back to reveal the knee belongs to First Bruce, an Australian in full Australian outback gear. We briefly hear a record of ‘Waltzing Mathilda’. He is sitting in a very hot, slightly dusty room with low wicker chairs, a table in the middle, big centre fan, and old fridge

Second Bruce [Graham Chapman]: Goodday, Bruce!

First Bruce [Eric Idle]: Oh, Hello Bruce!

Third Bruce [Michael Palin]: How are yer Bruce?

First Bruce: Bit crook, Bruce.

Second Bruce: Where’s Bruce?

First Bruce: He’s not here, Bruce.

Third Bruce: Blimey, s’hot in here, Bruce.

First Bruce: S’hot enough to boil a monkey’s bum!

Second Bruce: That’s a strange expression, Bruce.

First Bruce: Well Bruce, I heard the Prime Minister use it. S’hot enough to boil a monkey’s bum in ‘ere, your Majesty,’ he said and she smiled quietly to herself.

Third Bruce: She’s a good Sheila, Bruce and not at all stuck up.

Second Bruce: Ah, here comes the Bossfella now! – how are you, Bruce?

Enter fourth Bruce with English person, Michael

Fourth Bruce [John Cleese]: Goodday, Bruce, Hello Bruce, how are you, Bruce? Gentlemen, I’d like to introduce a chap from pommie land… who’ll be joining us this year here in the Philosophy Department of the University of Woolamaloo.

All: Goodday.

Fourth Bruce: Michael Baldwin – this is Bruce. Michael Baldwin – this is Bruce. Michael Baldwin – this is Bruce.

First Bruce: Is your name not Bruce, then?

Michael [Terry Jones]: No, it’s Michael.

Second Bruce: That’s going to cause a little confusion.

Third Bruce: Mind if we call you ‘Bruce’ to keep it clear?

Fourth Bruce: Well, Gentlemen, I think we’d better start the meeting. Before we start, though, I’ll ask the padre for a prayer.

First Bruce snaps a plastic dog-collar round his neck. They all lower their heads.

First Bruce: Oh Lord, we beseech thee, have mercy on our faculty, Amen!!

All: Amen!

Fourth Bruce: Crack the tubes, right! (Third Bruce starts opening beer cans) Er, Bruce, I now call upon you to welcome Mr. Baldwin to the Philosophy Department.

Second Bruce: I’d like to welcome the pommy bastard to God’s own earth, and I’d like to remind him that we don’t like stuck-up sticky-beaks here.

All: Hear, hear! Well spoken, Bruce!

Fourth Bruce: Now, Bruce teaches classical philosophy, Bruce teaches Haegelian philosophy, and Bruce here teaches logical positivism, and is also in charge of the sheepdip.

Third Bruce: What’s does new Bruce teach?

Fourth Bruce: New Bruce will be teaching political science – Machiavelli, Bentham, Locke, Hobbes, Sutcliffe, Bradman, Lindwall, Miller, Hassett, and Benet.

Second Bruce: Those are cricketers, Bruce!

Fourth Bruce: Oh, spit!

Third Bruce: Howls of derisive laughter, Bruce!

Fourth Bruce: In addition, as he’s going to be teaching politics, I’ve told him he’s welcome to teach any of the great socialist thinkers, provided he makes it clear that they were wrong.

They all stand up.

All: Australia, Australia, Australia, Australia, we love you. Amen!

They sit down.

Fourth Bruce: Any questions?

Second Bruce: New Bruce – are you a pooftah?

Fourth Bruce: Are you a pooftah?

Michael: No!

Fourth Bruce: No right, well gentlemen, I’ll just remind you of the faculty rules: Rule one – no pooftahs. Rule two, no member of the faculty is to maltreat the Abbos in any way whatsoever – if there’s anybody watching. Rule three – no pooftahs. Rule four – I don’t want to catch anyone not drinking in their room after lights out. Rule five – no pooftahs. Rule six – there is no rule six! Rule seven – no pooftahs. That concludes the reading of the rules, Bruce.

First Bruce: This here’s the wattle – the emblem of our land. You can stick it in a bottle or you can hold it in your hand.

All: Amen!

Fourth Bruce: Gentlemen, at six o’clock I want every man-Bruce of you in the Sydney Harbour Bridge room to take a glass of sherry with the flying philosopher, Bruce, and I call upon you, padre, to close the meeting with a prayer.

First Bruce: Oh Lord, we beseech thee etc. etc. etc., Amen.

All: Amen!

First Bruce: Right, let’s get some Sheilas.

An Aborigine servant bursts in with an enormous tray full of enormous steaks.

Fourth Bruce: OK.

Second Bruce: Ah, elevenses.

Third Bruce: This should tide us over ’til lunchtime.

Second Bruce: Reckon so, Bruce.

First Bruce: Sydney Nolan! What’s that! (points)

Cut to dramatic close-up of Fourth Bruce’s ear. Hold close-up. The superimposed arrow pointing to the ear.

Voice Over: Number nine. The ear.

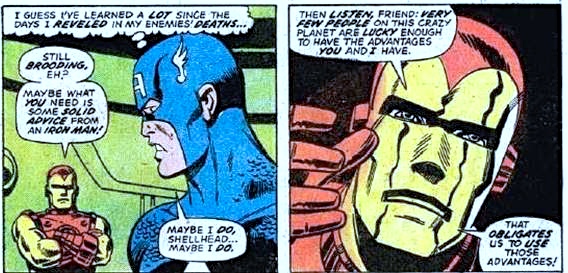

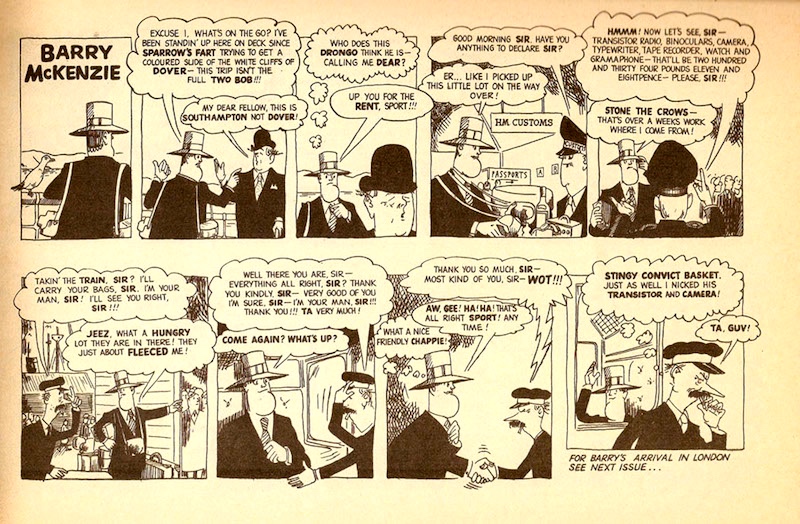

A still:

![]() (#4)

(#4)

The sketch was varied in a number of ways in performances and in the version that was recorded on the 1973 album Matching Tie and Handkerchief, where the sketch concluded with the whole cast singing “The Philosopher’s Song”, which is all about drinking:

Immanuel Kant was a real piss-ant who was very rarely stable.

Heidegger, Heidegger was a boozy beggar who could think you under the table.

David Hume could out-consume Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel.

And Wittgenstein was a beery swine who was just as sloshed as Schlegel.

There’s nothing Nieitzsche couldn’t teach ‘ya ’bout the raising of the wrist.

Socrates, himself, was permanently pissed.

John Stewart Mill, of his own free will, after half a pint of shandy was particularly ill.

Plato, they say, could stick it away, half a crate of whiskey every day!

Aristotle, Aristotle was a bugger for the bottle,

And Hobbes was fond of his Dram.

And Rene Descartes was a drunken fart: ‘I drink, therefore I am.’

Yes, Socrates himself is particularly missed;

A lovely little thinker, but a bugger when he’s pissed.

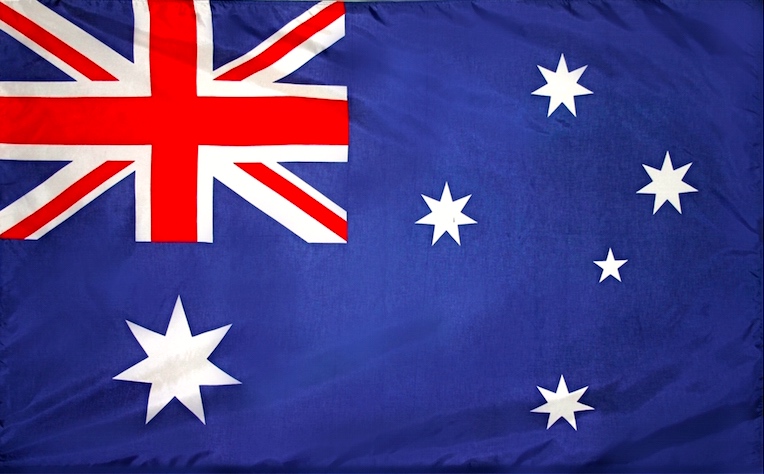

The name Bruce. Now from the site Waltzing More Than Matilda ~ Names with an Australian Bias of Democratic Temper, from 9/17/14, Famous Name: Bruce:

When the name Acacia was featured for Wattle Day, I mentioned that Monty Python made gentle fun of our national flower with their Bruces Sketch, where all the philosophy faculty at the (fictional) University of Woolloomooloo are named Bruce. This seems to be the origin of the notion that Bruce is a particularly Australian name.

![]() (#5)

(#5)

Acacia podalyrifolia, Queensland silver wattle

Barry Humphries has said that the inspiration for the Bruces Sketch was his Barry Mackenzie character, who began life as a comic strip in Private Eye. Barry Humphries’ television series, The Barry Humphries Scandals, was a precursor to Monty Python, and Eric Idle has cited Humphries as one of his comedy influences.

It’s rumoured, not implausibly, that Humphries himself suggested the name Bruce as an Australian signifier, either directly or indirectly. The name Bruce peaked in Australia in the 1930s, and in Britain slightly later, in the 1940s. Even at its height in the UK, it was only around the bottom of the Top 100, so it wasn’t nearly as common there.

Humphries was born in 1934, so had peers called Bruce. The most obvious example is Australian director Bruce Beresford (born 1940), who directed the Barry Mackenzie films. Like Barry Humphries, Bruce went to England in search of career opportunities, but was unable to break into the British film industry, and found success at home, with movies like Breaker Morant and Puberty Blues, and in North America with Driving Miss Daisy, and Black Robe.

The connection between Barry and Bruce continued when Humphries took the role of a great white shark named Bruce in the animated film, Finding Nemo. The American film-makers named Bruce, primarily not as an Australian reference, but after the shark in Jaws, whose models were all called Bruce after Steven Spielberg’s lawyer. Bruce the Shark does have an Australian accent though, and uses ockerisms like “Good on ya, mate!”.

From the United States, the name Bruce gained a different stereotype, being associated with homosexuality. The reasons are unclear, but one of the most popular theories is that it’s connected to the campy Batman television shows of the 1960s, as Batman’s real name is Bruce Wayne. Another is that it is from the 1960s parody song Big Bruce, where Bruce is a camp hairdresser.

Apart from these reasons, it does seem that the “tough guy” names of one generation are often seen as effeminate, dorky, or otherwise laughable by the next. Something to think about should you be considering one of today’s rugged baby names, such as Axel, Blade, Diesel, or Rowdy.

Barry Humphries. From Wikipedia:

John Barry Humphries … (born 17 February 1934) is an Australian comedian, actor, satirist, artist, and author. Humphries is best known for writing and playing his on-stage and television alter egos Dame Edna Everage and Sir Les Patterson. He is also a film producer and script writer, a star of London’s West End musical theatre, an award-winning writer and an accomplished landscape painter. For his delivery of dadaist and absurdist humour to millions, biographer Anne Pender described Humphries in 2010 as not only “the most significant theatrical figure of our time … [but] the most significant comedian to emerge since Charlie Chaplin”.

Humphries’ characters have brought him international renown, and he has appeared in numerous films, stage productions and television shows. Originally conceived as a dowdy Moonee Ponds housewife who caricatured Australian suburban complacency and insularity, Edna has evolved over four decades to become a satire of stardom, the gaudily dressed, acid-tongued, egomaniacal, internationally feted Housewife Gigastar, Dame Edna Everage.

![]() (#6)

(#6)

Humphries’ other major satirical character creation was the archetypal Australian bloke Barry McKenzie, who originated as the hero of a comic strip about Australians in London (with drawings by Nicholas Garland) which was first published in Private Eye magazine. The stories about “Bazza” (Humphries’ nickname, an Australian term of endearment for the name Barry) gave wide circulation to Australian slang, particularly jokes about drinking and its consequences (much of which was invented by Humphries), and the character went on to feature in two Australian films, in which he was portrayed by Barry Crocker.

Humphries’ other satirical characters include the “priapic and inebriated cultural attaché” Sir Les Patterson, who has “continued to bring worldwide discredit upon Australian arts and culture, while contributing as much to the Australian vernacular as he has borrowed from it”, gentle, grandfatherly “returned gentleman” Sandy Stone, iconoclastic 1960s underground film-maker Martin Agrippa, Paddington socialist academic Neil Singleton, sleazy trade union official Lance Boyle, high-pressure art salesman Morrie O’Connor and failed tycoon Owen Steele.

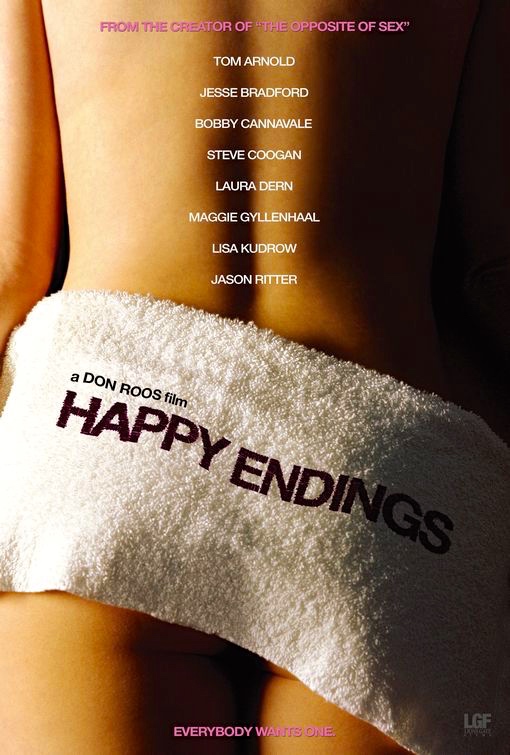

Barry McKenzie. From Wikipedia:

Barry McKenzie (full name: Barrington Bradman Bing McKenzie) is a fictional character created by the Australian comedian Barry Humphries (but suggested by Peter Cook) for a comic strip, written by Humphries and drawn by New Zealand artist Nicholas Garland in 1964, in the British satirical magazine Private Eye.

![]() (#7)

(#7)

The Private Eye comic strips were compiled into a book, The Wonderful World of Barry McKenzie, in which McKenzie travels to Britain to claim an inheritance. The book was published in London, but was banned in Australia with the Minister for Customs and Excise stating that it “relied on indecency for its humour”.

Two films followed.

The character was a parody of the boorish Australian overseas, particularly those residing in Britain – ignorant, loud, crude, drunk and punchy – although McKenzie also proved popular with Australians because he embodied some of their positive characteristics: he was friendly, forthright and straightforward with his British hosts, who themselves were often portrayed as stereotypes of pompous, arrogant, devious colonialists. McKenzie frequently employs euphemisms for bodily functions or sexual allusions, one of the most well-known being “technicolour yawn” (vomiting). The [1972] film popularised several Australian euphemisms and slang terms which are still used today in the Australian vernacular (such as “point Percy at the porcelain”, “sink the sausage” and “flash the nasty”). Some of the sayings were invented by Humphries, while other terms were borrowed from existing Australian slang such as “chunder” [vomit] and “up shit creek” (adopted by the Australian poetry magazine Shit Creek Review).

For a later posting, on Aussie masculinity (and class): aussieBum underwear, Shearing the Ram by Tom Roberts, and Slim Dusty.

![]()

![]()

(#2)

(#2)

(#2)

(#2)